Part of getting over it is knowing that you will never get over it.

- Anne Finger ("Past Due," 1990)

“What were they thinking?” is a favorite magazine and tabloid newspaper heading often used as a commentary over funny or bizarre photographs. But frequently when I think of the Swell Dames that I admire, I find myself wondering the same thing. What were they thinking? And what were they feeling as they faced the challenges, crossroads and choices that ultimately changed and shaped the trajectory of their lives?

Were they preparing dinner when their lover walked into the kitchen and said, “We need to talk”? Did their knees buckle when they realized that everything they’d worked for their entire lives was wiped out in a day because they trusted a con man, their own husband? What were they feeling as they watched their dream house float down the street in a once in a thousand year flood? After Noah’s Ark, God promised never to destroy the world again with water. Just don’t try “comforting” a woman from Texas or Florida right now with that biblical reference. Better yet, say nothing other than a prayer for what they are enduring, offer gratitude that you’re not and make a donation to the Red Cross.

Because there are no words when sorrow slaps you senseless with a sucker punch. There’s no self-help mantra, nor belief big enough to surmount the anguish at this moment. When the day after tomorrow arrives at each of our doors, and it will, there’s no metaphysical “Secret” on earth to help you come to grips with the unfathomable. All we know is that we are shocked, stunned, hurt, grieving, and groping with too many unknowns to consider and too many contingencies to handle.

“There was a time when my life seems so painful to me that reading about the lives of other women writers was one of the few things that could help. I was unhappy, and ashamed of it; I was baffled by my life,” Kennedy Fraser admits in her luminous collection of essays on women’s lives, Ornament and Silence. “Even now, I feel I should pretend that I was reading only these women’s fiction or their poetry—their lives as they chose to present them, alchemized as art. But that would be a lie. It was the private messages I really liked—the journals and letters, and autobiographies and biographies whenever they seemed to be telling the truth. I felt very lonely then, self-absorbed, shut off. I needed all this murmured chorus, this continuum of true life stories, to pull me through. They were like mothers or sisters to me, these literary women, many of them already dead; more than my own family, they seemed to stretch out a hand.”

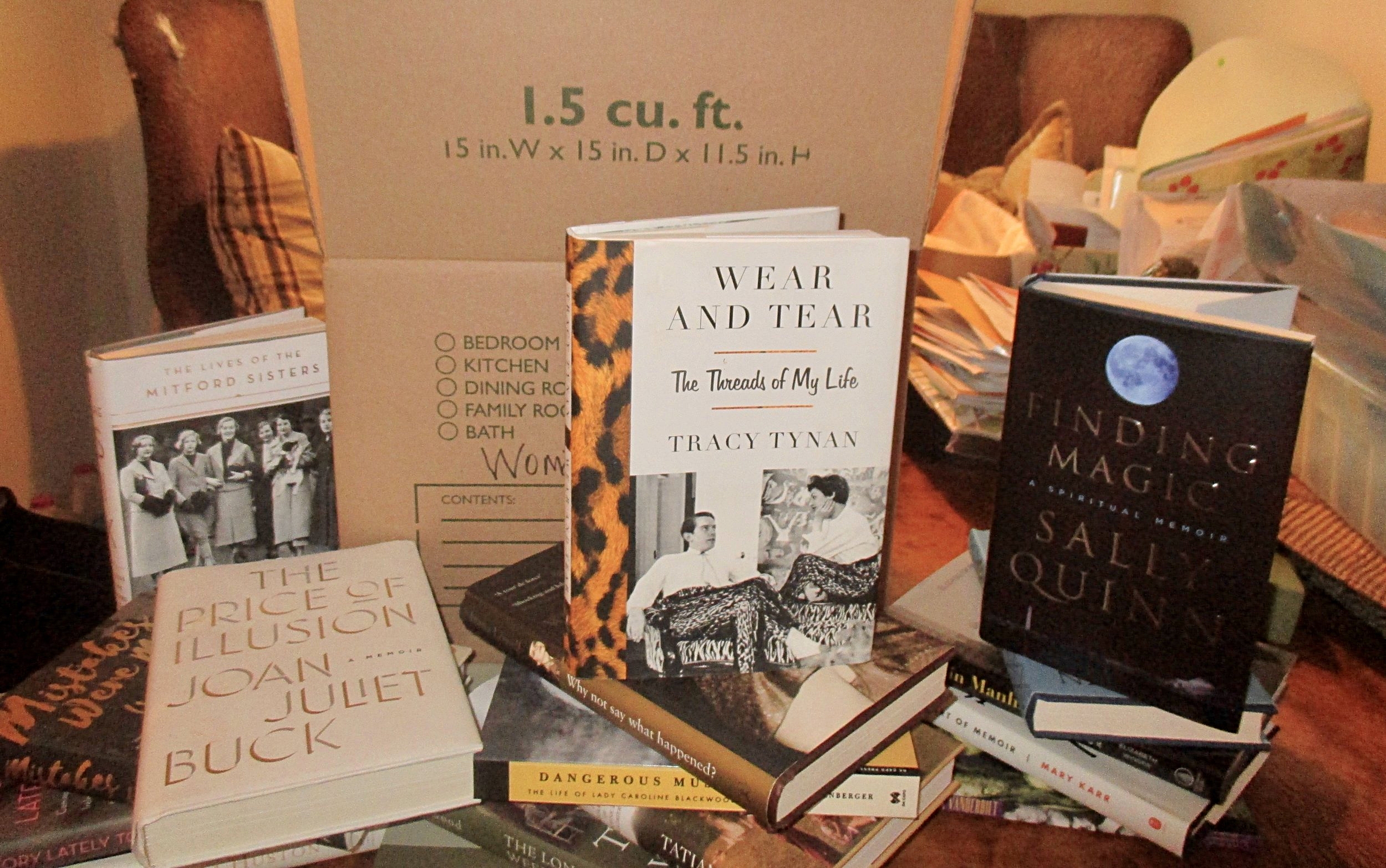

This summer, in a season when I was supposed to be preparing to move by winnowing out my belongings and books to pack, I seem to have done the exact reverse: accumulate new ones. Or I’ll pull out books from packed boxes that I forgot I even had. “Oh, that never should have been packed,” I’ll admonish the cats dozing on the boxes. I don’t know when I was planning to have time to read them all because I will be moving. Perhaps the real reason for this new cache is because I’m trying to reassure myself that there are plenty of women I admire who experienced the getting through the getting over stage of grief and change. “See,” I brace myself as I add another memoir to my stack of resilience, “You will, too.”

Unacknowledged grief demands that attention must be paid to its sorrow. However long it takes and at the most inconvenient times. But we will pay attention. It seems that writing my remembrance on Princess Diana’s death last week opened up an old wound, which I erroneously believed had been covered with scar tissue for the last decade. You see, I’d not made the connection between being in England to cover Diana’s funeral and the finding and buying of Sir Isaac Newton’s private chapel only a few days later, or at least I hadn't thought of those threads in a very long time. And this is how the dominoes fall: if I’d never gone to London to cover the funeral, I never would have taken a few extra days to visit Sir Isaac Newton’s private Chapel, which was for sale. If I’d never bought the Chapel, I never would have … there’s no happy ending at the end of this paragraph, so I won't go on. But the cause and effect chain reaction doesn’t need to be great to wreak serious damage. Did you know that just 29 dominoes could knock down the Empire State Building? (Thank you www.smithsonian.com)

And that is where my own Swell Dame found me to have a little chat. Setting the dominoes up. It went something like this. You will never get over losing Newton’s Chapel. Eve never got over losing Eden. But the only way you can move to the future is by being grateful that you once lived in Paradise and you created a beautiful Home there. The dream of Newton’s Chapel is your dream of home. You can create a new home for us. I’ll help you. There are some things we are not meant to get over. Sometimes we hold on to the grief of the Past because it’s the only way we know how to hold on to the ashes of Love.

That’s why I writing to you this week because I’m sure I’m not the only woman who’s shut herself down in order to shut her inconvenient emotions off from whatever we can’t face or accept just yet. I’d not even let myself cry really because I was afraid that once I started I wouldn’t be able to stop. But the Compassionate One has already intervened on our behalf. The Talmud tells us “Even when the gates of Heaven are closed to prayers, they are open to tears.” Far from being self-indulgent, crying is an ancient form of articulated prayer. In Catholic and Eastern Orthodox religions, tears have always been a special gift of the Holy Spirit; in the Hebrew Old Testament, an entire book of the Bible is devoted to crying—the Book of Lamentations.

For centuries in the west of Gaelic-speaking Ireland, particularly in Connemara, certain women, wise in the ways of the supernatural or “other” realms were taught the proper way to grieve with sound, or keen, which is a long, high-pitched wail of abandonment and grief strong enough to shatter glass. The language of keening is the passionate calling forth of exactly what it is that you dread and fear, to rise up and meet you face-to-face on the scorched battlefield of your devastated heart. The sob is the soul’s sacred battle cry for the Beloved to intervene, to help, to have mercy, to deliver you. To carry you off the battlefield. To bring you Home.

Keening women in "The Aran Fisherman's Drowned Child" by Frederick William Burton

To keen is to embrace those emotions too deep and too dark for words, struggling now for some, any form of expression. To let the sound of sorrow and waves of grief pass through you, picking up tempo and timbre as you go, is like breath on the reed of a woodwind or strings of a violin. To truly cry takes tremendous courage. A fiery anger wrestles in the pit of your gut; the despair catches in your throat; the fierce loneliness of the iron band of sorrow tightens across your chest.

Many of us resist the sacred relief of crying because the truth is, the act of crying physically hurts. Heartache is real. But we must trust that it hurts for a reason. We feel so alone. Bereft. We can’t go on we tell ourselves. But we must go on, we must take the next step, any step. Fill an empty box with your cherished books. For the love of all that is holy, do you really believe that God would leave us alone at such a moment? I don’t. I won’t and you can’t either. Because how else could we go on? And go on, we must. But I’ll never hush you, Sweetheart. I’d rather you howl at the moon. Heaven knows that I have.

Women had a lot to cry about during the Depression and the Home Front years. Keeping bodies and souls together with a continuous feed of courageous optimism and cheerful vivacity was considered vital to morale. Women’s magazines of this era acknowledged and provided regular remedies to soothe red faces and swollen eyes after having “a good cry.”

Here’s my favorite homemade après-crisis restorative. It calls for items you probably have in your refrigerator and cupboard—a cucumber-and-chamomile-tea rinse for the face that I call:

Sweet Mercy Medicinal

½ cucumber, peeled and seeded

¼ cup hot, prepared green tea

¼ cup hot, prepared chamomile tea

Puree the cucumber in a blender and strain the juice. Mix the teas together and add the cucumber juice. Stir well and refrigerate for at least half an hour. This mixture will keep a day or two in the fridge. If you’ve been crying on and off, dab your face with some, rinse with cool water, and then pat your face dry with your softest towel.

Also have on hand a pitcher of water with cucumber slices and drink from it frequently. Often when we’re emotionally distressed and wrung-out, we forget to do things as simple as sipping water while we slosh back the wine and whiskey. Reach for the water first, because dehydration can make you swoon.

“Heaven knows we need never be ashamed of our tears,” Charles Dickens wrote in Great Expectations (1860), “for they are rain upon the blinding dust of earth, overlying our hard hearts.”

Sending my dearest love and blessings on your courage, more than words can ever say,

XO SBB